“F…it. Let’s Go Get the Building”

It was 1986, and I remember when my Army unit commander, stationed to complete my Advanced Individual Training (AIT) in Fort Gordon, GA, informed me that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) 'had come a-calling.'

After months of inquiry, interviews, and agent visits to my family and friends, the Fingerprint Analyst I position at FBI Headquarters in Washington, D. C., was offered. At the time, I was stationed at Fort Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, completing my Advanced Individual Training (AIT) for the Army National Guard. The FBI assignment felt satisfying, and as I was still fresh from the rigorous basic training program at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, I envisioned myself as a fierce, Black female agent.

On the first day, all recruits convened at the FBI headquarters on Pennslyvania Avenue. When we met a few real agents, I was beside myself as we were all told to aspire to serve our country at the highest levels within the bureau. In my mind, I was already there. 'Federal Agent, FREEZE!' I envisioned yelling at a criminal. As we moved into the elevator, I was in full soldier/agent mode as we descended to our offices: Level B3, three levels below civilization.

As smooth as the ride was, it was a long trip from the upper levels where the real action was happening. It seemed like we were going down to the earth's core. 'How far down are we going?' I wondered.

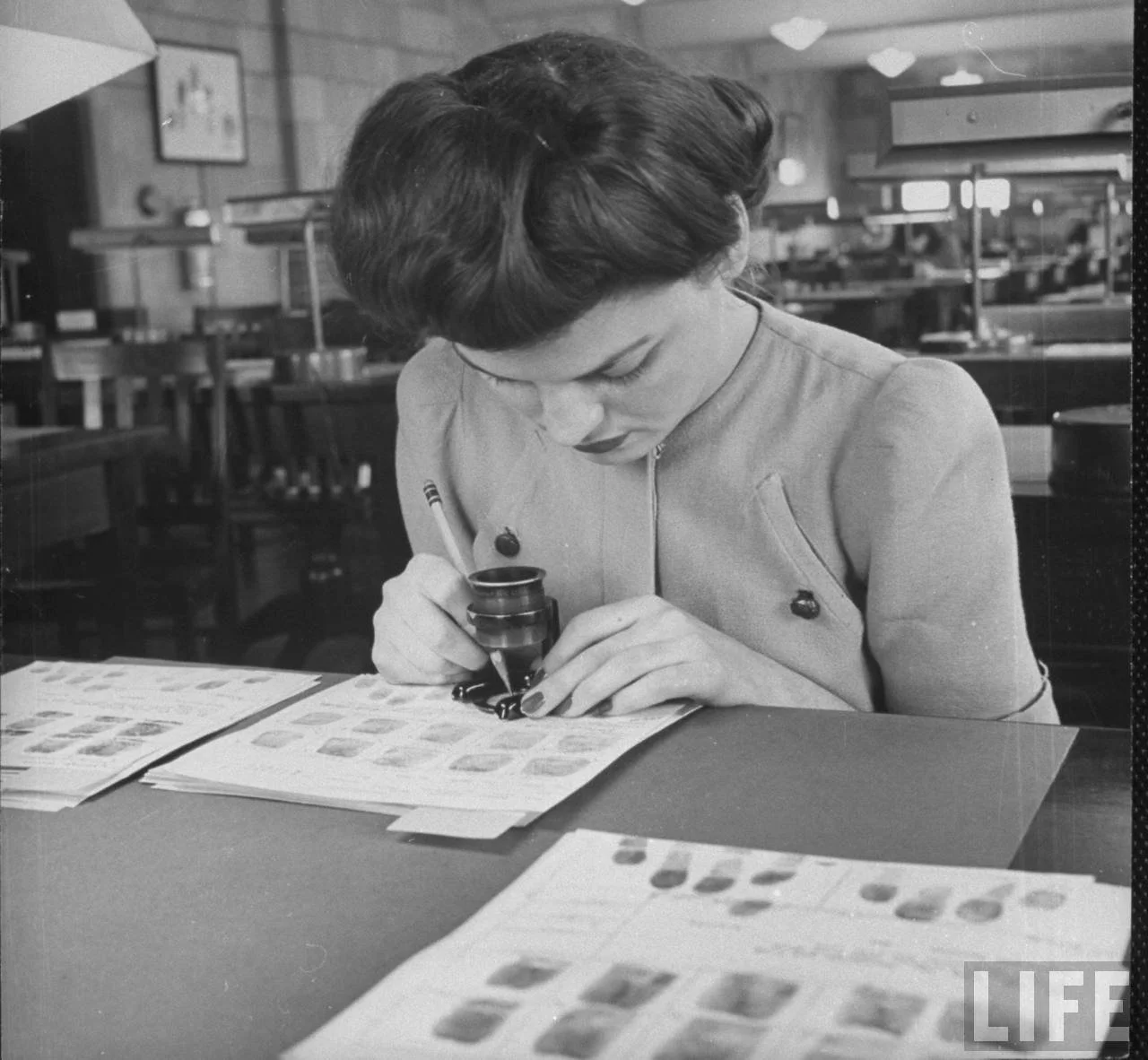

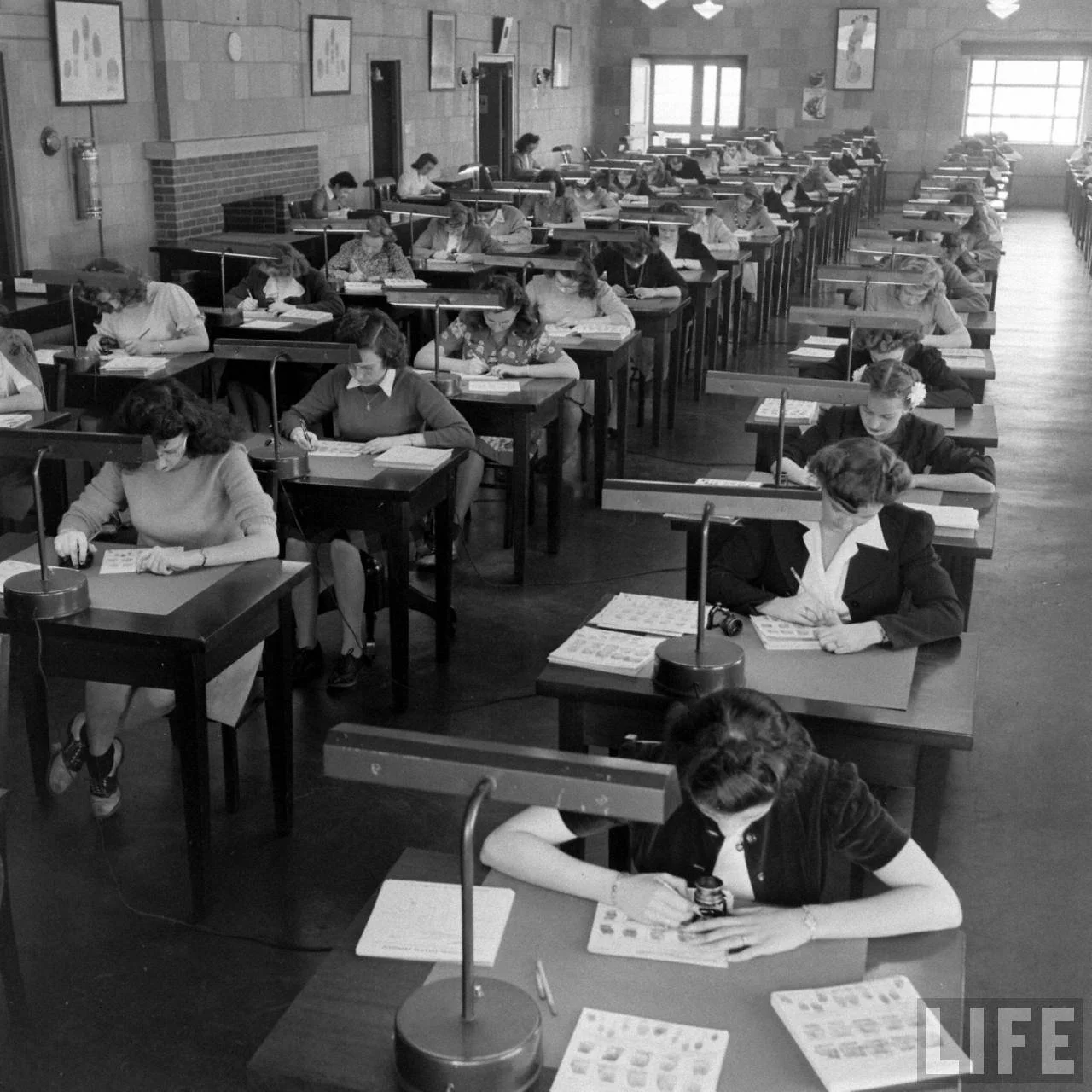

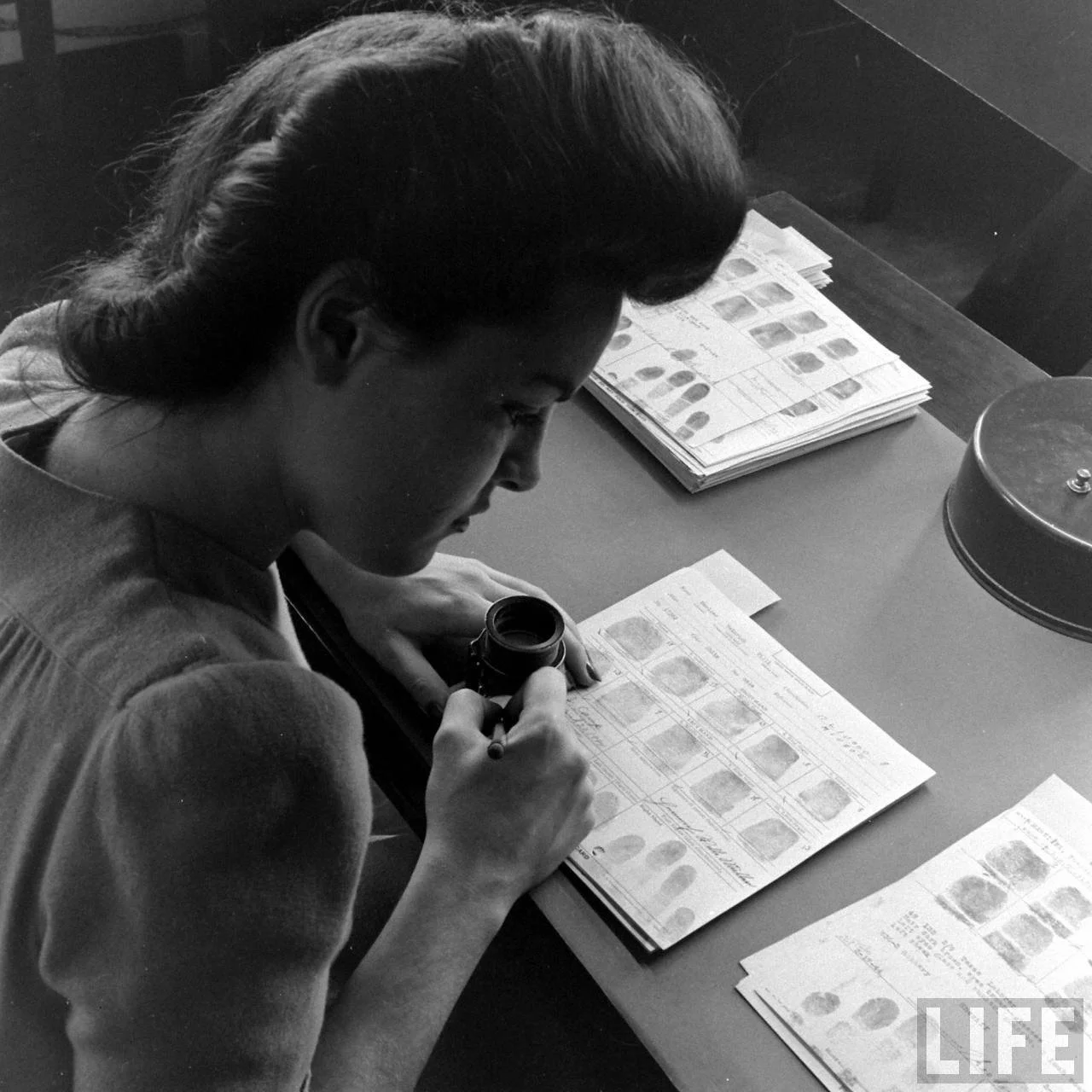

The elevator finally stopped, and we walked into a room that was about the size of half a football field. The constant buzzing and clicking of a conveyor belt with 12" x12" bundles of fingerprints moving around like an airport baggage carousel snaked the room from end to end. Throughout the carousel, other analysts were positioned on stools or at slanted desks, hunched over fingerprints with a magnifying glass, a fluorescent light, and .05" mechanical pencils. Several folks looked up at us, rolled their eyes, and bent back over their work.

Someone walked past us and said, 'Welcome to Hell.'

To say that the work was tedious and monotonous would be an understatement. However, I knew I had someone's life in my hands with each card I examined. Each indelible mark was measured and recorded, including cuts, burns, and scrapes. The work was complex and time-consuming; essentially, I would spend my entire day assigning numerical values according to the ridge patterns of loops, whorls, and arches I saw in the magnified fingerprints.

Even though I was literally in the bowels of the justice system, I understood the weight of the work. I could still imagine and feel the narrative of 'from fingerprint analyst to agent' coming to life until one particular day.

Because I was in the Army National Guard, I entered the bureau as a GS-3, which was about $24,000 a year. One afternoon, a co-worker walked past me, and she was elated. After working there for almost thirty years, she had just received a significant raise. Not shy about the details, she explained, 'I'm a GS-5 now, baby!'. My mouth fell open—a GS-5 made around $33,000 a year. And the most at that level she could earn was $41,000. She was sixty-two. I was eighteen at the time.

I remember feeling pride when I saw a Black male agent during our tour. As I'm thinking back, there was only one Black male agent. After finally noticing that there were primarily Black women in my area, they all started with the same aspirations to someday become an agent. All eventually gave up and settled on the social realities of civil service.

I put in my two-week notice the next day.

Over the years, I've discovered a natural aversion to stagnation and living below my potential. After working in corporate America, medium-sized companies, and startups, striking out as an entrepreneur provided me the most freedom to realize my potential. However, what I also found interesting is that the dynamic of working within a structure, a pre-designed organizational culture, was comforting at some level. Expectations were clear, and my job was to navigate either around or through them. Being alone was exciting, and just thinking about building the perfect environment where I could use 100% of my skills was powerful. I have discovered that while space can be liberating, filling a void with the proper foundation for success is daunting.

Doing the work I loved to do was easy when the work came to me. However, I choked when I had to go and find the contract, meet new people, and share what I do and why I'm the one to do it. On cue, as soon as someone asked, 'What do you do?' My answers felt robotic, and I felt like an imposter. Then, I'd be acutely aware that the individual I was talking to was looking over my shoulder, searching for a polite way of dumping me and moving on to who they wanted to meet. I felt small and irrelevant; eventually, I played small and kept myself irrelevant. It was easier to stay in the background and sort of blend in. This way, I could avoid criticism and scrutiny. As a GenX Black woman from the South, I came face-to-face with regular examples of racism and misogyny.

It was my family who pushed me to go further. My daughter Maya, in particular, had a terrible math phobia. She was so discouraged at one point after a teacher told her directly that she just wouldn’t be good enough for AP Geometry, even though Maya was willing to put in the extra work to learn what she needed to learn. The damage was done. Maya was so discouraged that she wanted to give up. As a self-anointed 'Mama Bear,' I rallied behind her and told her that quitting was not an option, even though this was scary and overwhelming. I shared with her that I was also scared of failing in this business and had often wanted to quit. We made a pact together that day.

Nobody quits, and we both push our goals with everything we have. We were 'ride or die'. Period. Her pathway was pretty straightforward, and mine felt gnarly. I had to accept that what I was doing wasn't working. That day, I made another pact with myself. 'I tried being invisible and blending in. That sucked. Now, it's my time to stand in the light and be fully out in the world.

We both went to work. Maya eventually graduated with a double Master's in Civil Engineering from the University of California - Berkeley. Berkeley! The Number 3 engineering school in the country! I have surpassed six figures in income but have experienced the pendulum swing mercilessly to five figures in one year. Being an entrepreneur is tough. Some days are fabulous, and others, you find yourself looking up and asking, ‘Really?!?’

I used to think, 'If my name was Brian and I was a white male, I'd have a freakin' building by now.' While some of that sentiment (or reality) may be true, I'm clear about the negative, self-reducing role I have contributed to that narrative. Now, I have developed the tools to help entrepreneurs build enough confidence to say, 'You know what? F...it. Let's go get the building' and believe it.

That's why Entre-SLAM exists:

I want you to have what you need to examine, celebrate, and leverage to activate your business vision fully. You're not doing anyone any favors by playing small. Hopefully, this blog and the stories along the way will guide and inspire you.

Ride or die, baby.

———————

Photo Credit:

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/fbi-fingerprint-files-facility-1944/